Today Nevadans celebrate Nevada Day. On this day in 1864 Nevada became a state.

Not only was Nevada “Battle Born,” as the flag proclaims, it was battle bred and born after a remarkably short gestation during the Civil War.

With Southern states seceding from the Union, in March 1861 President James Buchanan signed the bill declaring Nevada a territory. Lopped off from the western stretches of the Utah territory, the territory grew in population with the gold and silver booms of the Comstock Lode and other finds.

But its population in 1864 was still only about 30,000, just half of the required 60,000 for statehood and well short of the 100,000 that each member of Congress at the time represented.

Nevada was destined to become a state for the most compelling of reasons imaginable. No, not because the Union needed Nevada’s gold and silver to wage the ebbing Civil War. The Union got just as much revenue from the territory.

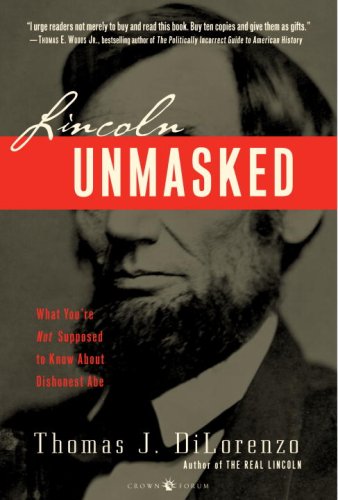

President Lincoln needed the votes in the election that occurred eight days after he declared: “Now, therefore, be it known, that I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, in accordance with the duty imposed upon me by the act of congress aforesaid, do hereby declare and proclaim that the said State of Nevada is admitted into the Union on an equal footing with the original states.”

President Lincoln needed the votes in the election that occurred eight days after he declared: “Now, therefore, be it known, that I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, in accordance with the duty imposed upon me by the act of congress aforesaid, do hereby declare and proclaim that the said State of Nevada is admitted into the Union on an equal footing with the original states.”

That is why Nevada became the 36th state and Utah did not become a state until 1896, while New Mexico and Arizona remained territories until 1912.

When Congress passed the Enabling Act for Nevada statehood on March 21, 1864, Lincoln was in a three way contest with Gen. John C. Fremont, a radical Republican, and Gen. George B. McClellan, a Democrat, both of whom Lincoln had relieved of their commands during the war.

It was feared the vote could be so divided and close that the election would have to be decided by the House of Representatives, where one more Republican representative could make all the difference.

According to retired Nevada State Archivist Guy Rocha, Nevada’s votes were needed to re-elect Lincoln and build support for his reconstruction policies, including the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery.

Fremont dropped out of the race in September after brokering a deal with Lincoln. The president then carried 60 percent of the Nevada vote and easily won re-election with 212 electoral votes to 21 for McClellan.

Nevada not only ratified the 13th Amendment, as well as the 14th Amendment, which guarantees due process and equal protection under law, but Nevada Sen. William M. Stewart played a key role in the drafting of the 15th Amendment stating the “right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

One of the first appeals for a separate territory came from a meeting in Gilbert’s saloon in Genoa in August 1857 instigated by Maj. William Ormsby, according to Thompson and West’s “History of Nevada,” published in 1881.

From this meeting came the appeal:

“The citizens inhabiting the valleys within the Great Basin of the American Continent, to be hereinafter described, beg leave respectfully to present for the earnest consideration of the President of the United States, and the members of both Houses of Congress this their petition; praying for the organization of a new Territory of the United States. We do not propose to come with any flourish of trumpets or multiply words in this memorial, but we propose simply to submit a few plain statements as the inducements and reasons which actuate us in making this appeal to those who have the power to remedy the existing difficulties and embarrassments under which we now labor and suffer.”

Among those difficulties and embarrassments was:

“In the winter-time the snows that fall upon the summits and spurs of the Sierra Nevada, frequently interrupt all intercourse and communications between the Great Basin and the State of California, and the Territories of Oregon and Washington, for nearly four months every year. During the same time all intercourse and communication between us and the civil authorities of Utah are likewise closed.

“Within this space of time, and indeed from our anomalous condition during all seasons of the year, no debts can be collected by law; no offenders can be arrested, and no crime can be punished except by the code of Judge Lynch, and no obedience to government can be enforced, and for these reasons there is and can be no protection to either life or property except that which may be derived from the peaceably disposed, the good sense and patriotism of the people, or from the fearful, unsatisfactory, and terrible defense and protection which the revolver, the bowie-knife, and other deadly weapons may afford us.”

Nevada’s path to statehood gained firm footing that same year when Brigham Young, the territorial governor of Utah and president of the Mormon Church, called on church members to leave what is now Nevada and other regions to assemble in Salt Lake City to prepare for an anticipated military confrontation with the federal government.

In 1858, “as a war measure directed at the Mormons,” Rocha recounts,

Congress’ Committee on Territories submitted a bill to create a territorial government called Sierra Nevada.

The name was shortened when the committee submitted its written reasons for creating the new territory: “to protect the public mails traveling within and through it; make safe and secure the great overland route to the Pacific as far as within its limits; restore friendly relations with the present hostile Indian tribes; contribute to the suppression of the Mormon power by the protection it might afford to its dissatisfied members; and (be) of material aid to our military operations. Thus satisfied and impressed, your committee respectfully report a bill for the formation of a new Territory … to be called the Territory of Nevada.”

Dan De Quille the 30-year staffer of the Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City stated the case a bit more colloquially in his book “The Big Bonanza.”

Dan De Quille

Occupying the western portion of the vast Utah Territory, the miners of the Comstock range were a long way from the longest arm of any law, so they resorted to making their own. At a meeting in Gold Hill on June 11, 1859, various “rules and regulations” were unanimously adopted.

Among the more ignoble, De Quille noted, was: “No Chinaman shall hold a claim in this district.”

The rest were of the customary Western laws — simple, swift and strict.

— “Any person who shall wilfully and with malice aforethought take the life of any person, shall, upon being duly convicted thereof, suffer the penalty of death by hanging.”

— “Any person found guilty of assault and battery, or exhibiting deadly weapons, shall, upon conviction, be fined or banished, as the jury may determine.”

De Quille — who like many of his ilk, time and locale was known to stretch the truth a bit — recounts one tale of terrible swift justice.

In August of 1859 two thieves by the names of George Ruspas and David Reise stole a yoke of cattle and attempted to sell them at a suspiciously low price. They were arrested, tried and sentenced by the jury of their peers to have their left ears cut off and be banished.

“Jim Sturtevant, an old resident of Washoe Valley, was appointed executioner,” De Quille writes. “He drew out a big knife, ran his thumb

along the blade, and not finding its edge just to his mind, gave it a few rakes across a rock. He then walked up to Reise and taking a firm hold on the upper part of the organ designated by the jury, shaved it off, close up, at a single slash. As he approached Ruspas, the face of that gentleman was observed to wear a cunning smile. He seemed very much amused about something. The executioner, however, meant business, and tossing Reise’s ear over to the jury, who sat at the root of the pine, he went after that of Ruspas, whose eyes were following every motion made and whose face wore the expression of that of a man about to say or do a good thing.

“Sturtevant pulled aside the fellow’s hair, which he wore hanging down about his shoulders, and lo! there was no left ear, it having been parted with on some previous and similar occasion. Here was a fix for the executioner! His instructions were to cut off the fellow’s left ear, but there was no left ear on which to operate. The prisoner now looked him in the face and laughed aloud.

“The joke was so good that he could no longer restrain himself. Sturtevant appealed to the jury for instructions. The jury were enjoying the scene not a little, and being, in a good humor, said that they would reconsider their sentence; that rather than anyone should be disappointed the executioner might take off the prisoner’s right ear, if he had one. The smile faded out of the countenance of Ruspas as he felt Sturtevant’s fingers securing a firm hold on the top of his right ear. An instant after, Sturtevant gave a vigorous slash, and then tossed Ruspas’ ear over to the jury, saying as he did so, that they now had a pair of ears that were ‘rights and lefts’ and therefore properly mated.

“This little ceremony over, the pair of thieves were directed to take the road leading over the Sierras to the beautiful ‘Golden State.’”

After the territory was created, Lincoln promptly appointed party loyalists to fill offices in the newly carved out territory. James Nye of New York was appointed governor and Orion Clemens became secretary, bringing along his younger brother Samuel to be an assistant.

Nye had campaigned for Lincoln in the previous election. Orion Clemens had studied in the St. Louis law office of Edward Bates, who became Lincoln’s attorney general.

The younger Clemens brother described with some probable embellishment their arrival in Carson City:

“We arrived, disembarked, and the stage went on. It was a ‘wooden’ town; its population two thousand souls. The main street consisted of four or five blocks of little white frame stores which were too high to sit down on, but not too high for various other purposes; in fact, hardly high enough. They were packed close together, side by side, as if room were scarce in that mighty plain. …

“We were introduced to several citizens, at the stage-office and on the way up to the Governor’s from the hotel — among others, to a Mr. Harris, who was on horseback; he began to say something, but interrupted himself with the remark:

“’I’ll have to get you to excuse me a minute; yonder is the witness that swore I helped to rob the California coach — a piece of impertinent intermeddling, sir, for I am not even acquainted with the man.’

“Then he rode over and began to rebuke the stranger with a six-shooter, and the stranger began to explain with another. … I never saw Harris shoot a man after that but it recalled to mind that first day in Carson.

“This was all we saw that day, for it was two o’clock, now, and according to custom the daily ‘Washoe Zephyr’ set in; a soaring dust-drift about the size of the United States set up edgewise came with it, and the capital of Nevada Territory disappeared from view.”

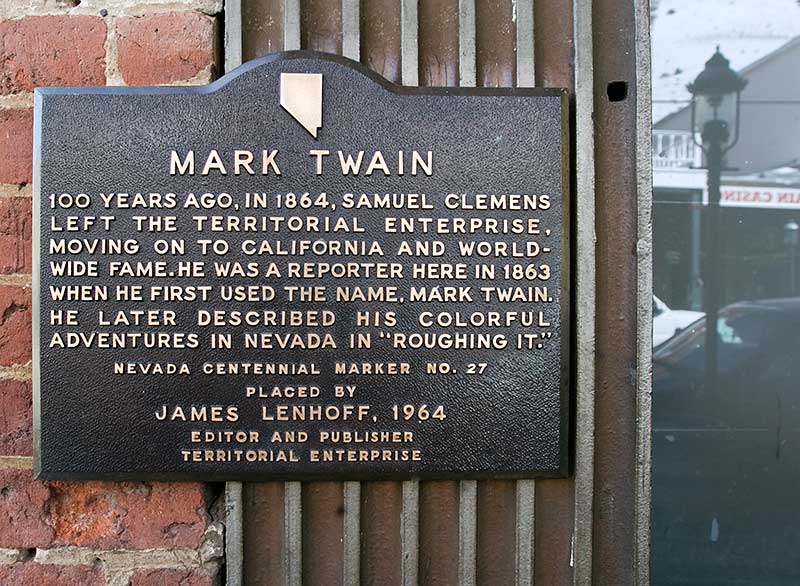

By the time Sam Clemens penned that introduction to Carson City, he had adopted the pen name Mark Twain.

.jpg)

Mark Twain

Sam Clemens first used that nom de plume on Feb. 3, 1863, in dispatches from Carson City for the Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City. Ten years later he would offer the quaint explanation about how it was derived from his days as a riverboat pilot on the ever-shifting Mississippi River, where the leadsman would take soundings to determine the depth. Twelve feet of clearance was needed for the draft of the paddleboats, thus the leadsman would call out for the log book, “Mark twain,” or two fathoms.

But newspapering has always been parching work for penurious pay, the more Nevada centric and less clean-cut explanation might be closer to the truth, which Twain was seldom averse to stretching.

Twain biographer Andrew Hoffman writes, “People who knew Sam in Nevada said that he arrived at the pseudonym by entering a saloon and calling out in the leadsman’s singsong intonation ‘Mark twain!’ — meaning the bartender should pour two drinks and mark them down on the debit ledger.”

Gov. Nye arrived on July 7, 1861, without mentioning gunfire or zephyrs. He declared the Nevada officially a territory on July 11. A census found 16,374 souls residing in said territory.

In an ironic turn of events, one of the first acts of the newly elected territorial legislature was to declare gambling illegal. According to Russell Elliott’s “History of Nevada,” Gov. Nye delivered an impassioned appeal to lawmakers:

“I particularly recommend that you pass stringent laws to prevent gambling. It holds all the seductive vices extent, I regard that of gambling as the worst. It holds out allurement hard to be resisted. It captivates and ensnares the young, blunts all the moral sensibilities and ends in utter ruin.”

The law carried a fine of $500 and two years in jail.

While the lawmakers for the territory were outlawing what would one day generate more wealth than all the gold and silver mines, they also were still dithering over what name the future state would bear. At one point the legislature approved an act “to frame a Constitution and State Government for the State of Washoe.” The names of Humboldt and Esmeralda also were bandied about until Nevada won out.

But the path from territory to statehood was nearly derailed by an old familiar issue that resonates 150 years later — mining taxes.

At first the residents of the territory voted by a margin of 4-to-1 for statehood in September 1863. But in January 1864 a Constitution that would have taxed mining at the same rate as other enterprises was voted down by a similar 4-to-1 margin.

Then in July 1864 a revised document that changed mining taxes to “net proceeds” — allowing deduction of expenses — passed on a vote of 10,375 to 1,284.

With time running out before the November election, the new Constitution was telegraphed to Washington, D.C., at a cost of $3,416.77.

Nevada’s motto — “All for Our Country” — and its Constitution reflect the Battle Born nature of the times and divided country.

The Constitution contains a seemingly incongruous amalgam of the Declaration of Independence and a loyalty oath:

“All political power is inherent in the people[.] Government is instituted for the protection, security and benefit of the people; and they have the right to alter or reform the same whenever the public good may require it. But the Paramount Allegiance of every citizen is due to the Federal Government in the exercise of all its Constitutional powers … The Constitution of the United States confers full power on the Federal Government to maintain and Perpetuate its existance [existence], and whensoever any portion of the States, or people thereof attempt to secede from the Federal Union, or forcibly resist the Execution of its laws, the Federal Government may, by warrant of the Constitution, employ armed force in compelling obedience to its Authority.”

Both of Nevada’s new senators arrived in Washington in time to vote for the 13thAmendment abolishing slavery and the new state’s lawmakers approved it on Feb. 16, 1865.

Sen. Stewart later wrote:

“It was understood that the Government at Washington was anxious that Nevada should become a State in order that her Senators and Representative might assist in the adoption of amendments to the Constitution in aid of the restoration of the Southern States after the Union should be vindicated by war. Another and very important factor in inducing the people to vote for statehood was the unsatisfactory judiciary condition under a territorial form of government. … The morning after I took my seat in the Senate I called upon President Lincoln at the White House. He received me in the most friendly manner, taking me by both hands, and saying: ‘I am glad to see you here. We need as many loyal States as we can get, and, in addition to that, the gold and silver in the region you represent has made it possible for the Government to maintain sufficient credit to continue this terrible war for the Union. I have observed such manifestations of the patriotism of your people as assure me that the Government can rely on your State for such support as is in you power.’”

Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865.

The original territory created in 1861 was added to in 1862 and 1866 by slicing off vertical chunks of western Utah. In 1867 the southern-most part of the state, now mostly Clark County, was added by taking the westernmost reaches of the Arizona Territory. Until 1909, Clark County was a part of Lincoln County.

On Nov. 2, 1864, The New York Herald published a glowing account of the state’s admission and what it meant for the nation.

The article began:

“The proclamation of President Lincoln, published in the Herald of Monday, absorbs the Territory of Nevada, with its untold wealth of riches in gold, silver and other minerals, into the ever swelling bosom of the United States. Nevada, but yesterday an isolated place on which but little public interest concentrated, has suddenly become a place of paramount importance, as a new and valuable state of the Union.

“Today we give a map of the new State in connection with this sketch of the history of its progress and wealth. The State is called ‘Nevada,’ from the old Spanish nomenclature, that word signifying ‘snowy,’ from the word ‘nieve,’ which means snow in the Castilian language.”

The article concludes breathlessly: “There can be no doubt that the future of the new State will be as propitious as its beginning. With so much available wealth in its bosom, it is natural that it must attract intelligent and enterprising people to go and settle there.”

Nevada did not have an official flag until 1905. That version had the word Nevada in the middle with the words Silver at the top and Gold at the bottom with rows of stars between the words. The Battle Born flag was not adopted until 1929. It was revised slightly in 1991 to make the word Nevada easier to read.

When Nevada became a state, its new Constitution contained a so-called Disclaimer Clause, just like every other new state being admitted, in which the residents of the territory were required to “forever disclaim all right and title to the unappropriated public lands lying within said territory, and that the same shall be and remain at the sole and entire disposition of the United States.”

Nevada’s enabling act also states that the land “shall be sold,” with 5 percent of proceeds going to the state.

The land was never sold and to this day various federal agencies control approximately 85 percent of the land in the state. The Disclaimer Clause was repealed by the voters in 1996, but nothing has been done about it since by any governor, congressman or attorney general.

A version of this blog first appeared on Oct. 31, 2014.

Footnote: Nevada and I share this birthday, but the Nevada is slightly older.

.jpg)